Investors Need a Tactical Strategy to Navigate Turbulent Headwinds

By Dave Valdez, ChFC & Marc Nichols, CIMA

The year-to-date performance of the overall market, increasing geopolitical tensions, increasing gas prices, and the highest inflation numbers in four decades are enough to scare off investors from adding to their portfolios or deploying idle cash. How does an investor get started in with the negative headwind and all too frequent triple digit volatility days in the market? Below, we’ll discuss a tactic we recommend here at Arbor.

Dollar-Cost Averaging (DCA)

Many investors will experience ‘analysis paralysis’ or simply bury their heads in the sand. Although sitting on the sidelines may be considered a strategy, it also comes with opportunity cost associated with sitting in cash. Sitting in cash is also known as “going backwards” with inflation numbers above 8%. The purchasing power of the dollar decreases over time and, with the Federal Reserve’s dovish policies infusing the market over the past three years with low interest rates, the money supply inflated prices in almost every sector in the economy.

At Arbor, one strategy that we employ to help ease investors into the market is dollar-cost averaging (DCA). This strategy allows an investor to utilize cash on the sidelines with a disciplined, tactical strategy. This tactic will buy into the market every 30, 60, 90-day interval that fits the needs of the investor. By doing so, it will reduce the risk that the investor will be affected by a lump sum buy into the market. With the market whipsawing, the investor will be able to capitalize when prices come down significantly. The investor will tactically build their position until they are fully invested in the market. This takes discipline, patience, and a long-term strategic plan.

Stick it Out or Sell to Cash?

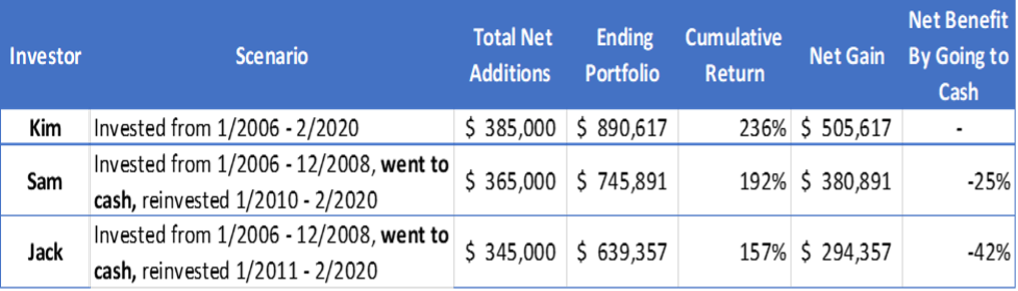

By way of example, here are three long-term investors who started to invest in 2006. For simplicity, this example doesn’t include the impact of taxes, inflation, and rebalancing. Dividends and capital gains are assumed to be reinvested.

Scenario 1: Kim

Kim invested $100,000 in March 2006 in an account that was allocated to 85% stock (SPDR¨ S&P 500 ETF) and 15% bonds (iShares Core US Aggregate Bond ETF)1. She invested $5,000 per quarter until the end of February 2020. Over this 14+ year period, Kim’s net investment was $385,000 and by the end of last month, her portfolio was worth over $890,000.

Despite having gone through the financial crisis, Kim’s portfolio has increased 236% over this period.

Scenario 2: Sam

Now let’s look at another investor, Sam, who had the same account as Kim but decided to sell and go to cash at the end of 2008. Was he better off?

If Sam cashed out at the end of December 2008, his account would be worth about $129,000 despite investing $160,000. Even though he lost principal, Sam managed to bail before the bottom of the crisis, which was March 2009.

Fast forward to January 2010 – the market rebound is seven months old, and Sam feels comfortable getting back in. He takes his proceeds from the 2008 liquidation and reinvests them with the same 85/15 investment mix as before. Sam resumes dollar-cost averaging $5,000 per quarter.

By the end of February 2020, Sam’s portfolio would be worth roughly $746,000. Kim’s portfolio is ahead by nearly $150,000.

Scenario 3: Jack

In the last scenario, let’s look at Jack, who’s strategy was just like Sam’s, but Jack waited until January 2011 to get back in with the same investment and contribution strategy as before. By the end of February 2020, Jack’s account would be worth $639,000 – over $250,000 less than Kim’s account and more than $105,000 less than Sam’s!

Loss Aversion & Recency Bias

Behavioral finance studies reveal that our own biases can adversely affect the performance of our portfolios. An example is loss aversion. Loss aversion is a cognitive bias where individual investors believe the pain of losing money feels worse than gaining the same amount of money. Awareness of loss aversion illuminates the need for a tactical dollar-cost averaging strategy.

Additionally, with the recent tumultuous market, recency bias can also play its role in affecting investor behavior. Recency bias is the tendency to place more emphasis on experiences that are most fresh – giving the recent market volatility greater importance. This can cause investors to deviate from their long-term financial plans, which can be detrimental to their success.

Dollar-Cost Averaging: Simple Yet Powerful

Dollar-cost averaging is a simple concept but requires discipline to act on. In times of heightened psychological stress and market volatility, it can help curb the impulse to make decisions that may keep you from achieving long-term financial success. (Take it from Kim!)

At Arbor, we do not believe in market timing. We are advocates of being in the market for the long-term. When an investor has a strategy that is aligned with their financial plan, we can stay focused on their overall long-term investment and holistic goals. Dollar-cost averaging is one of the many ways we replace emotions with a process and maintain investment discipline during volatile markets.